Introduction

Welcome to the first article in my series about Javascript deobfuscation. I won’t be going in-depth regarding practical deobfuscation techniques; that’ll be reserved for later articles. Rather, this post serves as a brief overview of the state of Javascript obfuscation, different methods of analysis, and provides resources to learn more about reverse engineering Javascript.

What is Obfuscation?

Definition

Obfuscation is a series of code transformations that turn human-readable code into something that is deliberately difficult for a human to understand, while (for the most part) still maintaining its original functionality. Code authors may choose to obfuscate their code for many reasons, including but not limited to:

- To make it harder to modify, debug, or reproduce (e.g. some javascript-based games or programs)

- To hide malicious intent (e.g. malware)

- To enhance security, i.e obscuring the logic behind javascript-based challenges or fingerprinting (e.g. ReCAPTCHA, Shape Security, PerimeterX, Akamai, DataDome)

Example

For example, the obfuscation process can convert this human-readable script:

js1console.log("Hello");Into something incomprehensible to humans:

js 1var _0x3b8ba1 = _0x57e2;

2function _0x57e2(_0x23db1e, _0x36111b) {

3 var _0x3bbee9 = _0x5936();

4 return (

5 (_0x57e2 = function (_0x194e56, _0x27d4e2) {

6 _0x194e56 = _0x194e56 - 0x17e;

7 var _0x2b5447 = _0x3bbee9[_0x194e56];

8 return _0x2b5447;

9 }),

10 _0x57e2(_0x23db1e, _0x36111b)

11 );

12}

13(function (_0x3d5379, _0x27d8c9) {

14 var _0x26235b = _0x57e2,

15 _0x556a19 = _0x3d5379();

16 while (!![]) {

17 try {

18 var _0x15999f =

19 parseInt(_0x26235b(0x183)) / 0x1 +

20 parseInt(_0x26235b(0x185)) / 0x2 +

21 (parseInt(_0x26235b(0x194)) / 0x3) *

22 (-parseInt(_0x26235b(0x18d)) / 0x4) +

23 parseInt(_0x26235b(0x188)) / 0x5 +

24 (-parseInt(_0x26235b(0x18b)) / 0x6) *

25 (-parseInt(_0x26235b(0x187)) / 0x7) +

26 -parseInt(_0x26235b(0x182)) / 0x8 +

27 -parseInt(_0x26235b(0x195)) / 0x9;

28 if (_0x15999f === _0x27d8c9) break;

29 else _0x556a19["push"](_0x556a19["shift"]());

30 } catch (_0x3cc29a) {

31 _0x556a19["push"](_0x556a19["shift"]());

32 }

33 }

34})(_0x5936, 0x4bc84);

35var _0x5cff45 = (function () {

36 var _0x5a2bb8 = !![];

37 return function (_0x2e90c1, _0x495f04) {

38 var _0x1ac9d1 = _0x5a2bb8

39 ? function () {

40 var _0x261249 = _0x57e2;

41 if (_0x495f04) {

42 var _0x3c800c = _0x495f04[_0x261249(0x198)](_0x2e90c1, arguments);

43 return (_0x495f04 = null), _0x3c800c;

44 }

45 }

46 : function () {};

47 return (_0x5a2bb8 = ![]), _0x1ac9d1;

48 };

49 })(),

50 _0x1ea628 = _0x5cff45(this, function () {

51 var _0x4f765e = _0x57e2;

52 return _0x1ea628[_0x4f765e(0x17f)]()

53 ["search"](_0x4f765e(0x18e))

54 ["toString"]()

55 ["constructor"](_0x1ea628)

56 [_0x4f765e(0x192)](_0x4f765e(0x18e));

57 });

58_0x1ea628();

59function _0x5936() {

60 var _0x7289e8 = [

61 "Hello\x20World!",

62 "toString",

63 "log",

64 "__proto__",

65 "2888432EGELDh",

66 "516645rknrWL",

67 "trace",

68 "928870xUjHrE",

69 "error",

70 "27965akgdka",

71 "2813765Wufwlg",

72 "return\x20(function()\x20",

73 "warn",

74 "48zUcTLM",

75 "bind",

76 "2668xZhNIu",

77 "(((.+)+)+)+$",

78 "prototype",

79 "console",

80 "table",

81 "search",

82 "length",

83 "615NtfKnc",

84 "6908400qvcpUL",

85 "exception",

86 "constructor",

87 "apply",

88 ];

89 _0x5936 = function () {

90 return _0x7289e8;

91 };

92 return _0x5936();

93}

94var _0x27d4e2 = (function () {

95 var _0x494152 = !![];

96 return function (_0x2d8431, _0x2bbb6a) {

97 var _0x1528ad = _0x494152

98 ? function () {

99 if (_0x2bbb6a) {

100 var _0x4f8607 = _0x2bbb6a["apply"](_0x2d8431, arguments);

101 return (_0x2bbb6a = null), _0x4f8607;

102 }

103 }

104 : function () {};

105 return (_0x494152 = ![]), _0x1528ad;

106 };

107 })(),

108 _0x194e56 = _0x27d4e2(this, function () {

109 var _0x2df84e = _0x57e2,

110 _0x50a5eb;

111 try {

112 var _0x458538 = Function(

113 _0x2df84e(0x189) + "{}.constructor(\x22return\x20this\x22)(\x20)" + ");"

114 );

115 _0x50a5eb = _0x458538();

116 } catch (_0x55824d) {

117 _0x50a5eb = window;

118 }

119 var _0x22e34f = (_0x50a5eb[_0x2df84e(0x190)] =

120 _0x50a5eb[_0x2df84e(0x190)] || {}),

121 _0x4b7f35 = [

122 _0x2df84e(0x180),

123 _0x2df84e(0x18a),

124 "info",

125 _0x2df84e(0x186),

126 _0x2df84e(0x196),

127 _0x2df84e(0x191),

128 _0x2df84e(0x184),

129 ];

130 for (

131 var _0x24f5c9 = 0x0;

132 _0x24f5c9 < _0x4b7f35[_0x2df84e(0x193)];

133 _0x24f5c9++

134 ) {

135 var _0x126b34 =

136 _0x27d4e2[_0x2df84e(0x197)][_0x2df84e(0x18f)][_0x2df84e(0x18c)](

137 _0x27d4e2

138 ),

139 _0x427a50 = _0x4b7f35[_0x24f5c9],

140 _0xdec475 = _0x22e34f[_0x427a50] || _0x126b34;

141 (_0x126b34[_0x2df84e(0x181)] = _0x27d4e2[_0x2df84e(0x18c)](_0x27d4e2)),

142 (_0x126b34[_0x2df84e(0x17f)] =

143 _0xdec475["toString"][_0x2df84e(0x18c)](_0xdec475)),

144 (_0x22e34f[_0x427a50] = _0x126b34);

145 }

146 });

147_0x194e56(), console[_0x3b8ba1(0x180)](_0x3b8ba1(0x17e));Yet, believe it or not, both of these scripts have the exact same functionality! You can test it yourself: both scripts output

Hello Worldto the console.

The State of Javascript Obfuscation

There are many available javascript obfuscators, both closed and open-source. Here’s a small list:

Open-Source

Closed-Source

For further reading on the why and how’s of Javascript Obfuscation, I recommend checking out the Jscrambler blog posts. For now, though, I’ll shift the topic towards reverse engineering.

How is Obfuscated Code Analyzed?

In general, most reverse engineering/deobfuscation techniques fall under two categories: static analysis and dynamic analysis

Static Analysis

Static analysis refers to the inspection of source code without actually executing the program. An example of static analysis is simplifying source code with Regex.

Dynamic Analysis

Dynamic analysis refers to the testing and analysis of an application during run time/evaluation. An example of dynamic analysis is using a debugger.

Static vs. Dynamic Analysis Use-Cases

Since static analysis does not execute code, it makes it ideal for analyzing untrusted scripts. For example, when analyzing malware, you may want to use static analysis to avoid infection of your computer.

Dynamic analysis is used when a script is known to be safe to run. Debuggers can be powerful tools for reverse engineering, as they allow you to view the state of the program at different points in the runtime. Additionally, dynamic analysis can be (and often is) used for malware analysis too, but only after taking proper security precautions (i.e sandboxing).

Static and dynamic analysis are powerful when used together. For example, debugging a script containing a lot of junk code can be difficult. Or, the code may contain anti-debugging protection (e.g. infinite debugger loops). In this case, someone may first use static inspection of source code to simplify the source code, then proceed with dynamic analysis using the modified source.

Introducing Babel

Babel is a Javascript to Javascript compiler. The functionalities included with the Babel framework make it exceptionally useful for any javascript deobfuscation use case, since you can use it for static analysis and dynamic analysis!

Let me give a short explanation of how it works:

Javascript is an interpreted programming language. For Javascript to be interpreted by an engine (e.g. Chrome’s V8 engine or Firefox’s Spidermonkey) into machine code, it is first parsed into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). After that, the AST is used to generate machine-readable byte-code, which is then executed.

Babel works in a similar fashion. It takes in Javascript code, parses it into an AST, then outputs javascript based on that AST.

Okay, sounds interesting. But what even is an AST?

Definition: Abstract Syntax Tree

An Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) is a tree-like structure that hierarchically represents the syntax of a piece of source code. Each node of the tree represents the occurrence of a predefined structure in the source code. Any piece of source code, from any programming language, can be represented as an AST.

Note: Even though the concepts behind an AST are universal, different programming languages may have a different AST specifications based on their capabilities.

Some practical uses of ASTs include:

- Validating Code

- Formatting Code

- Syntax Highlighting

And, of course, due to the more verbose nature of ASTs relative to plaintext source code, it makes them a great tool for reverse engineering 😁

Unfortunately, I won’t be giving a more in-depth definition of ASTs. This is for the sake of time, and since that’d be more akin to the subject of compiler theory than deobfuscation. I’d prefer to get right into explaining the usage of Babel as quickly as possible. However, I’ll leave you with some resources to read up more about ASTs (which probably offer a better explanation than I could muster anyway):

Wikipedia - Abstract Syntax Trees How JavaScript works: Parsing, Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs) + 5 tips on how to minimize parse time

How Babel Works

Babel can be installed the same way as any other NodeJS package. For our purposes, the following packages are relevant:

@babel/core This encapsulates the entire Babel compiler API.

@babel/parser The module Babel uses to parse Javascript source code and generate an AST

@babel/traverse The module that allows for traversing and modifying the generated AST

@babel/generator The module Babel uses to generate Javascript code from the AST.

@babel/types A module for verifying and generating node types as defined by the Babel AST implementation.

When compiling code, Babel goes through three main phases:

- Parsing => Uses

@babel/parserAPI - Transforming => Uses

@babel/traverseAPI - Code Generation => Uses

@babel/generatorAPI

I’ll give you a (very) short summary of each of these phases:

Stages of Babel

Phase #1: Parsing

During this phase, Babel takes source code as an input and outputs an AST. Two stages of parsing are Lexical Analysis and Syntactic Analysis.

To parse code into an AST, we make use of @babel/parser. The following is an example of parsing code from a file, sourcecode.js:

1const parser = require("@babel/parser");

2const code = fs.readFileSync("sourcecode.js", "utf-8");

3let ast = parser.parse(code);You can read more about the parsing phase here: Babel Plugin Handbook - Parsing Babel Docs - @babel/parser

Phase 2: Transforming

The transformation phase is the most important phase. During this phase, Babel takes the generated AST and traverses it to add, update, or remove nodes. All the deobfuscation transformations we write are executed in this stage. This stage will be the main focus of future tutorials.

Phase 3: Code Generation

The code generation phase takes in the final AST and converts it back to executable Javascript.

The Babel Workflow

This section will not discuss any practical deobfuscation techniques. It will only detail the general process of analyzing source code. I’ll be using an unobfuscated piece of code as an example.

When deobfuscating Javascript, I typically follow this workflow:

- Visualization

- Analysis

- Writing the Deobfuscator

Phase 1: Visualization with AST Explorer

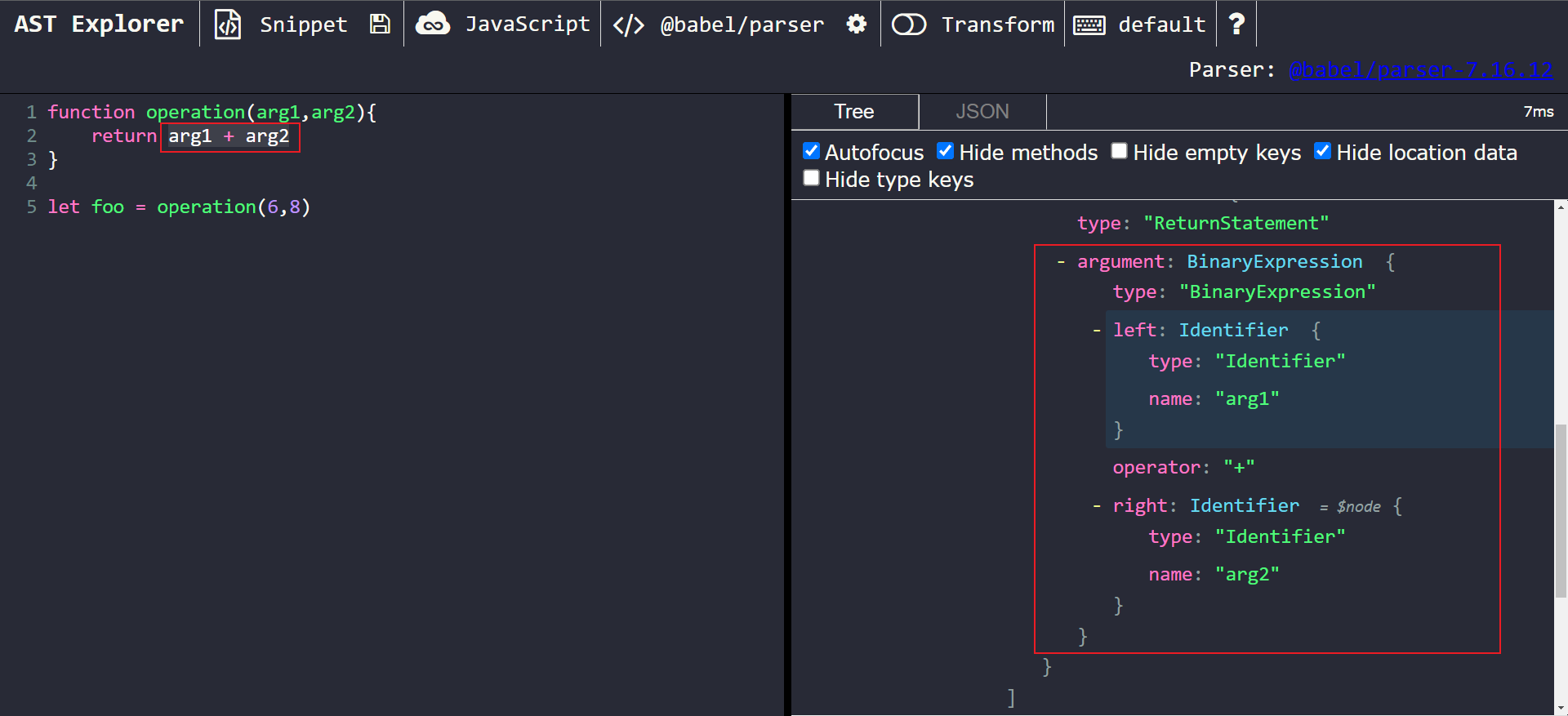

Before we can write any plugins for a deobfuscator, we should always first visualize the code’s AST. To help us with that, we will leverage an online tool: AstExplorer.net.

AST Explorer serves as an interactive AST playground. It allows you to choose a programming language and parser. In this case, we would select Javascript as the programming language and @babel/parser as the parser. After that, we can paste some source code into the window and inspect the generated AST on the right-hand side.

As an example, I’ll use this snippet:

javascript1function operation(arg1, arg2) {

2 let step1 = arg1 + arg2;

3}

4

5let foo = operation(6, 8);The generated AST looks like this:

javascript 1{

2 "type": "File",

3 "start": 0,

4 "end": 78,

5 "loc": {

6 "start": {

7 "line": 1,

8 "column": 0

9 },

10 "end": {

11 "line": 5,

12 "column": 24

13 }

14 },

15 "errors": [],

16 "program": {

17 "type": "Program",

18 "start": 0,

19 "end": 78,

20 "loc": {

21 "start": {

22 "line": 1,

23 "column": 0

24 },

25 "end": {

26 "line": 5,

27 "column": 24

28 }

29 },

30 "sourceType": "module",

31 "interpreter": null,

32 "body": [

33 {

34 "type": "FunctionDeclaration",

35 "start": 0,

36 "end": 52,

37 "loc": {

38 "start": {

39 "line": 1,

40 "column": 0

41 },

42 "end": {

43 "line": 3,

44 "column": 1

45 }

46 },

47 "id": {

48 "type": "Identifier",

49 "start": 9,

50 "end": 18,

51 "loc": {

52 "start": {

53 "line": 1,

54 "column": 9

55 },

56 "end": {

57 "line": 1,

58 "column": 18

59 },

60 "identifierName": "operation"

61 },

62 "name": "operation"

63 },

64 "generator": false,

65 "async": false,

66 "params": [

67 {

68 "type": "Identifier",

69 "start": 19,

70 "end": 23,

71 "loc": {

72 "start": {

73 "line": 1,

74 "column": 19

75 },

76 "end": {

77 "line": 1,

78 "column": 23

79 },

80 "identifierName": "arg1"

81 },

82 "name": "arg1"

83 },

84 {

85 "type": "Identifier",

86 "start": 24,

87 "end": 28,

88 "loc": {

89 "start": {

90 "line": 1,

91 "column": 24

92 },

93 "end": {

94 "line": 1,

95 "column": 28

96 },

97 "identifierName": "arg2"

98 },

99 "name": "arg2"

100 }

101 ],

102 "body": {

103 "type": "BlockStatement",

104 "start": 29,

105 "end": 52,

106 "loc": {

107 "start": {

108 "line": 1,

109 "column": 29

110 },

111 "end": {

112 "line": 3,

113 "column": 1

114 }

115 },

116 "body": [

117 {

118 "type": "ReturnStatement",

119 "start": 32,

120 "end": 50,

121 "loc": {

122 "start": {

123 "line": 2,

124 "column": 1

125 },

126 "end": {

127 "line": 2,

128 "column": 19

129 }

130 },

131 "argument": {

132 "type": "BinaryExpression",

133 "start": 39,

134 "end": 50,

135 "loc": {

136 "start": {

137 "line": 2,

138 "column": 8

139 },

140 "end": {

141 "line": 2,

142 "column": 19

143 }

144 },

145 "left": {

146 "type": "Identifier",

147 "start": 39,

148 "end": 43,

149 "loc": {

150 "start": {

151 "line": 2,

152 "column": 8

153 },

154 "end": {

155 "line": 2,

156 "column": 12

157 },

158 "identifierName": "arg1"

159 },

160 "name": "arg1"

161 },

162 "operator": "+",

163 "right": {

164 "type": "Identifier",

165 "start": 46,

166 "end": 50,

167 "loc": {

168 "start": {

169 "line": 2,

170 "column": 15

171 },

172 "end": {

173 "line": 2,

174 "column": 19

175 },

176 "identifierName": "arg2"

177 },

178 "name": "arg2"

179 }

180 }

181 }

182 ],

183 "directives": []

184 }

185 },

186 {

187 "type": "VariableDeclaration",

188 "start": 54,

189 "end": 78,

190 "loc": {

191 "start": {

192 "line": 5,

193 "column": 0

194 },

195 "end": {

196 "line": 5,

197 "column": 24

198 }

199 },

200 "declarations": [

201 {

202 "type": "VariableDeclarator",

203 "start": 58,

204 "end": 78,

205 "loc": {

206 "start": {

207 "line": 5,

208 "column": 4

209 },

210 "end": {

211 "line": 5,

212 "column": 24

213 }

214 },

215 "id": {

216 "type": "Identifier",

217 "start": 58,

218 "end": 61,

219 "loc": {

220 "start": {

221 "line": 5,

222 "column": 4

223 },

224 "end": {

225 "line": 5,

226 "column": 7

227 },

228 "identifierName": "foo"

229 },

230 "name": "foo"

231 },

232 "init": {

233 "type": "CallExpression",

234 "start": 64,

235 "end": 78,

236 "loc": {

237 "start": {

238 "line": 5,

239 "column": 10

240 },

241 "end": {

242 "line": 5,

243 "column": 24

244 }

245 },

246 "callee": {

247 "type": "Identifier",

248 "start": 64,

249 "end": 73,

250 "loc": {

251 "start": {

252 "line": 5,

253 "column": 10

254 },

255 "end": {

256 "line": 5,

257 "column": 19

258 },

259 "identifierName": "operation"

260 },

261 "name": "operation"

262 },

263 "arguments": [

264 {

265 "type": "NumericLiteral",

266 "start": 74,

267 "end": 75,

268 "loc": {

269 "start": {

270 "line": 5,

271 "column": 20

272 },

273 "end": {

274 "line": 5,

275 "column": 21

276 }

277 },

278 "extra": {

279 "rawValue": 6,

280 "raw": "6"

281 },

282 "value": 6

283 },

284 {

285 "type": "NumericLiteral",

286 "start": 76,

287 "end": 77,

288 "loc": {

289 "start": {

290 "line": 5,

291 "column": 22

292 },

293 "end": {

294 "line": 5,

295 "column": 23

296 }

297 },

298 "extra": {

299 "rawValue": 8,

300 "raw": "8"

301 },

302 "value": 8

303 }

304 ]

305 }

306 }

307 ],

308 "kind": "let"

309 }

310 ],

311 "directives": []

312 },

313 "comments": []

314}We can observe that even for this small little program, the AST representation is incredibly verbose. It’s composed of different types of nodes (FunctionDeclarations, ExpressionStatements, Identifiers, CallExpressions, etc.), and many nodes also have a sub node. To transform the AST, we’ll be making use of the Babel traverse package to recursively traverse the tree and modify nodes.

Phase 2: Coming Up With The Transformation Logic/Pseudo-code

This isn’t an obfuscated file, but we’ll still write a plugin to demonstrate the traverse package’s functionality.

Let’s assign ourselves an arbitrary goal of transforming the script to replace all occurrences of arithmetic addition operators (+) with arithmetic multiplication operators (*). That is, the final script should look like this:

1function operation(arg1, arg2) {

2 return arg1 * arg2;

3}

4

5let foo = operation(6, 8);Determining the Target Node Type(s)

First, we need to determine what our node type(s) of interest are. If we highlight a section of the code, AST explorer will automatically expand that node on the right-hand side. In our case, we want to focus on the arg1 + arg2 operation. After highlighting that piece of code, we’ll see this:

We can see that arg1 + arg2 has been parsed into a BinaryExpression node. This node has the following properties:

typestores the node’s type, in this case:BinaryExpressionleftstores the information for the left side of the expression, in this case: thearg1identifier.rightstores the information for the right side of the expression, in this case: thearg2identifier.operatorstores the operator, in this case:+.

Our goal is to replace all + operators in the script with a * operator, so it makes sense that our node type of interest is a BinaryExpression.

Now that we have our target node type, we need to figure out how we’ll transform them

Transformation Logic

To reiterate: we know that we’re looking for BinaryExpressions. Each BinaryExpression has a property, operator. We want to edit this property to * if it is a +.

The logical process would therefore look like this:

- Parse the code to generate an AST.

- Traverse the AST in search of

BinaryExpressions. - If one is encountered, check that its operator is currently equal to

+. If it isn’t, skip that node. - If the operator is equal to

+, set the operator to*.

Now that we understand the logic, we can write it as code

Phase 3: Writing the Transformation Code

To parse the tree, we will use the @babel/parser package as previously demonstrated. To traverse the generated AST and modify the nodes, we’ll make use of @babel/traverse.

To target a specific node type during traversal, we’ll use a visitor[https://github.com/jamiebuilds/babel-handbook/blob/master/translations/en/plugin-handbook.md#visitors].

From the Babel Plugin Handbook:

Visitors are a pattern used in AST traversal across languages. Simply put they are an object with methods defined for accepting particular node types in a tree.

To target nodes of type BinaryExpression, our visitor would like like this:

1const changeOperatorVisitor = {

2 BinaryExpression(path) {

3 // transformations here ...

4 },

5};Now, every time a BinaryExpression is encountered, the BinaryExpression(path) method will be called.

Inside the BinaryExpression(path) method of our visitor, we can add code for any checks and transformations.

Each visitor method takes in a parameter, path, which holds the path to the node being visited. To access the actual properties of the node, we must use path.node.

Our first step in our transformation would be to check that the operator property of the node is a +. We can do that like this:

1const changeOperatorVisitor = {

2 BinaryExpression(path) {

3 if (path.node.operator == "+") {

4 // continue with transformations...

5 } else {

6 return; // Skip the node

7 }

8 },

9};If it is a +, we can set it to *.

1const changeOperatorVisitor = {

2 BinaryExpression(path) {

3 // Check if operator is +

4 if (path.node.operator == "+") {

5 // Set operator as *

6 path.node.operator = "*";

7 } else {

8 return; // Skip the node

9 }

10 },

11};And our visitor is complete! Now we just need to call it on the generated AST. But first, let’s generate the AST:

javascript 1const parser = require("@babel/parser");

2const generate = require("@babel/generator").default;

3const traverse = require("@babel/traverse").default;

4const types = require("@babel/types");

5// Set the source code

6const code = `

7function operation(arg1, arg2) {

8 return arg1 * arg2;

9}

10let foo = operation(6, 8);

11`;

12// Parse the source code into an AST

13let ast = parser.parse(code);After that, we can paste our visitor into the source code. To traverse the AST using the visitor, we’ll use the traverse method from the @babel/traverse package. That would look like this:

1const parser = require("@babel/parser");

2const generate = require("@babel/generator").default;

3const traverse = require("@babel/traverse").default;

4const types = require("@babel/types");

5// Set the source code

6const code = `

7function operation(arg1, arg2) {

8 return arg1 * arg2;

9}

10let foo = operation(6, 8);

11`;

12// Parse the source code into an AST

13let ast = parser.parse(code);

14

15// Visitor for modifying operator of BinaryExpression

16const changeOperatorVisitor = {

17 BinaryExpression(path) {

18 // Check if operator is +

19 if (path.node.operator == "+") {

20 // Set operator as *

21 path.node.operator = "*";

22 } else {

23 return; // Skip the node

24 }

25 },

26};

27

28traverse(ast, changeOperatorVisitor);Finally, we’ll use the generate method from the @babel/generator package to generate the final code from the modified AST. We can also output the resulting code to a file, but I’ll just log it to the console for simplicity.

So, our final transformation script looks like this:

Babel Transformation Script

javascript 1const parser = require("@babel/parser");

2const generate = require("@babel/generator").default;

3const traverse = require("@babel/traverse").default;

4const types = require("@babel/types");

5// Set the source code

6const code = `

7function operation(arg1, arg2) {

8 return arg1 * arg2;

9}

10let foo = operation(6, 8);

11`;

12// Parse the source code into an AST

13let ast = parser.parse(code);

14

15// Visitor for modifying operator of BinaryExpression

16const changeOperatorVisitor = {

17 BinaryExpression(path) {

18 // Check if operator is +

19 if (path.node.operator == "+") {

20 // Set operator as *

21 path.node.operator = "*";

22 } else {

23 return; // Skip the node

24 }

25 },

26};

27

28traverse(ast, changeOperatorVisitor);

29

30let finalCode = generate(ast).code;

31

32console.log(finalCode);This will output the following to the console:

javascript1function operation(arg1, arg2) {

2 return arg1 * arg2;

3}

4

5let foo = operation(6, 8);And we can see that the code has been successfully transformed to replace + operators with * operators!

Why use Babel for Deobfuscation?

So, why should we use Babel as a deobfuscation tool as opposed to other static analysis tools like Regex?

Here are a few reasons:

-

Ast is less error-prone.

- For large chunks of code, writing transformations can become incredibly tedious due to the edge cases. For example, it’s difficult to account for the scope and state of variables when using regex. For example, two different variables can share the same name if they’re in different scopes:

1//Scope 1:

2{

3 let foo = 123;

4 {

5 let foo = 321;

6 console.log(foo);

7 }

8 console.log(foo);

9}Eventually, regular expressions will become very convoluted when you have to account for edge cases; whether it be scope or tiny variations in syntax. Babel doesn’t have this problem, as you can use built-in functionality to make transformations with respect to scope and state.

-

The Babel API has a lot of useful features.

Here are a few useful things you can do with the built-in Babel API:

- Easily target certain nodes

- Handle scope when renaming/replacing variables

- Easily get initial values and references of variables

- Node validation, generation, cloning, replacement, removal

- Find paths to ancestor and descendant nodes based on test conditions

- Containers/Lists: Check if a node is in a container/list, and get all of its siblings

-

Good for static and dynamic analysis

- Inherently, parsing the code into an AST and applying transformations will not execute the code. But Babel also has the functionality to evaluate nodes (ex. BinaryExpressions) and return their actual value. Babel can also generate code from nodes, which can be evaluated with

evalor the NodeJS VM.

- Inherently, parsing the code into an AST and applying transformations will not execute the code. But Babel also has the functionality to evaluate nodes (ex. BinaryExpressions) and return their actual value. Babel can also generate code from nodes, which can be evaluated with

Conclusion + Additional Resources

That was a short demonstration of transforming a piece of code with Babel! The next articles will be more in-depth and include practical cases of reversing obfuscation techniques you might encounter in the wild.

For the sake of time, I didn’t go too deep into the behind-the-scenes of Babel or all of its API methods. In the future, I may decide to update this article or write a new one with more detailed explanations, examples, and documentation. But, I really recommend getting a solid fundamental understanding of Babel’s features before continuing on in this series. Most notably, I didn’t cover the usage of the @babel/types package in this article, but it will be utilized in future ones. I’d recommend giving these resources a look:

Official Babel Docs Babel Plugin Handbook Video: @babel/how-to

Here are links to the other articles in this series:

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Reversing Various String Concealing Techniques

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Converting Bracket Notation => Dot Notation for Property Accessors

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Constant Folding/Binary Expression Simplification

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Constant Folding/Binary Expression Simplification

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Replacing References to Constant Variables with Their Actual Value

-

Deobfuscating Javascript via AST: Removing Dead or Unreachable Code

You can also view the source code for all my deobfuscation tutorial posts in this repository

Okay, that’s all I have for you today. I hope that this article helped you learn something new. Thanks for reading, and happy reversing!